A federal judge in Washington, D.C. has issued a strong rebuke to the U.S. Department of Justice, raising concerns over due process violations after the Trump administration deported over 200 Venezuelan nationals under the rarely used Alien Enemies Act of 1798.

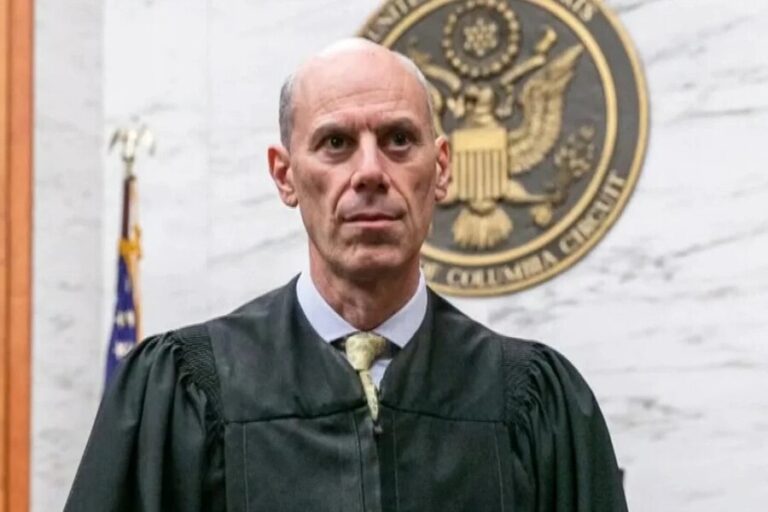

Chief District Judge James Boasberg expressed sharp criticism during a courtroom hearing on Friday, after learning that two deportation flights to El Salvador proceeded despite his verbal order to halt them. The judge had issued the order on Saturday, the same day the administration invoked the centuries-old law to justify the removals.

“I made it very clear what you had to do,” Judge Boasberg told Drew Ensign, the attorney representing the Justice Department. “Did you not understand my statements in that hearing?”

The two flights, carrying more than 200 Venezuelan nationals, departed the U.S. hours after President Trump issued a proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act—a wartime law that grants the president broad powers to detain and deport foreign nationals from enemy nations. The administration claims the deportees were affiliated with Tren de Aragua, a violent Venezuelan gang.

Boasberg blocked the administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act and issued an immediate order to stop the deportations. However, the Justice Department later claimed the flights had already exited U.S. airspace at the time of the order, arguing the judge had no jurisdiction to force their return.

“You did tell them it was an order from me to turn the planes around… to bring back people to the United States? You understood that?” Boasberg asked Ensign during Friday’s proceedings. “Did you understand that when I said ‘do that immediately,’ I meant it?”

Ensign responded, “I understood your intent to be what you were announcing would be binding,” but argued that since the order was issued verbally and not in written form, it was not legally enforceable.

Boasberg rejected that argument and reminded the government that while it may continue deportations, it may not do so under the authority of the Alien Enemies Act. He also accused the administration of acting with undue haste, stating that the presidential proclamation appeared to be “essentially signed in the dark” and followed immediately by the rapid removal of migrants.

The judge questioned why the administration proceeded so quickly, suggesting Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had prior knowledge of the proclamation. “It’s impossible this could have happened within two hours,” he said. Ensign later confirmed that ICE was indeed informed ahead of time.

Boasberg went on to raise constitutional questions about the Trump administration’s use of the 18th-century law, particularly its potential for violating due process. He pressed the government on what mechanisms exist for individuals to challenge their deportation if they were misidentified or not gang members.

“What happens if someone is not a member of Tren de Aragua or not a Venezuelan citizen or a U.S. citizen? How do they challenge their removal?” he asked. The Justice Department did not provide a direct answer.

In a broader hypothetical, Boasberg asked whether the president could declare that Chinese fishing vessels were invading U.S. waters and then proceed to detain and deport all Chinese fishermen. Ensign confirmed that such action would be legally permissible under the Alien Enemies Act.

Ensign also argued that individuals deported under the act still retain the ability to challenge their removal or detention—even if they are held in Salvadoran prisons. However, Boasberg voiced skepticism over how detainees could meaningfully challenge their removal once they are no longer on U.S. soil.

“If the detainees are entitled to some sort of hearing, some sort of individualized process… what is the standard for review of the executive’s evidence?” the judge asked. He emphasized that deference to executive authority should not be automatic, especially when civil liberties are at stake.

Boasberg also questioned why the Justice Department had not utilized the Alien Terrorist Removal Court—a tribunal established by Congress in 1996 to handle the removal of suspected terrorists. Despite its existence, no case has ever been brought to the court.

“If you determine that an alien is an alien enemy under the AEA and may be summarily removed, aren’t you precluding that due process challenge?” the judge asked, highlighting the constitutional implications of the administration’s actions.

Boasberg indicated he is considering narrowing the scope of his temporary restraining order that currently blocks all deportations under the Alien Enemies Act. He suggested that removals could proceed in cases where individuals voluntarily admit gang affiliation or do not contest their deportation.

At the same time, Boasberg asked both parties to submit further legal arguments on how the government could implement administrative proceedings that offer individualized hearings and legal reviews for each affected migrant.

“We are a long way from the government being willing to provide people with this process,” said Lee Gelernt, an attorney representing the plaintiffs. Gelernt welcomed the judge’s proposal for hearings but insisted that judicial oversight remains necessary to prevent executive overreach.

Boasberg’s ruling has sparked debate across legal and political circles about the scope of presidential authority, the use of wartime laws in peacetime immigration enforcement, and the constitutional protections owed to non-citizens.

The Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act has drawn criticism for its suddenness and lack of transparency, with many civil rights advocates warning that it sets a dangerous precedent.

The case remains ongoing, and further hearings are expected in the coming weeks. For now, the fate of the deported Venezuelans remains uncertain, and the question of whether due process protections were violated continues to dominate legal discourse.